When I first noticed an Instagram account obviously copying our work in July 2024, I tried to keep my zen. Also, it was not the first time something like this happened, as I’ve described in this post. But I won’t lie: It did hurt. the thing Magazine is my baby. And it felt unsettling—existentially, mostly in a capitalist sense.

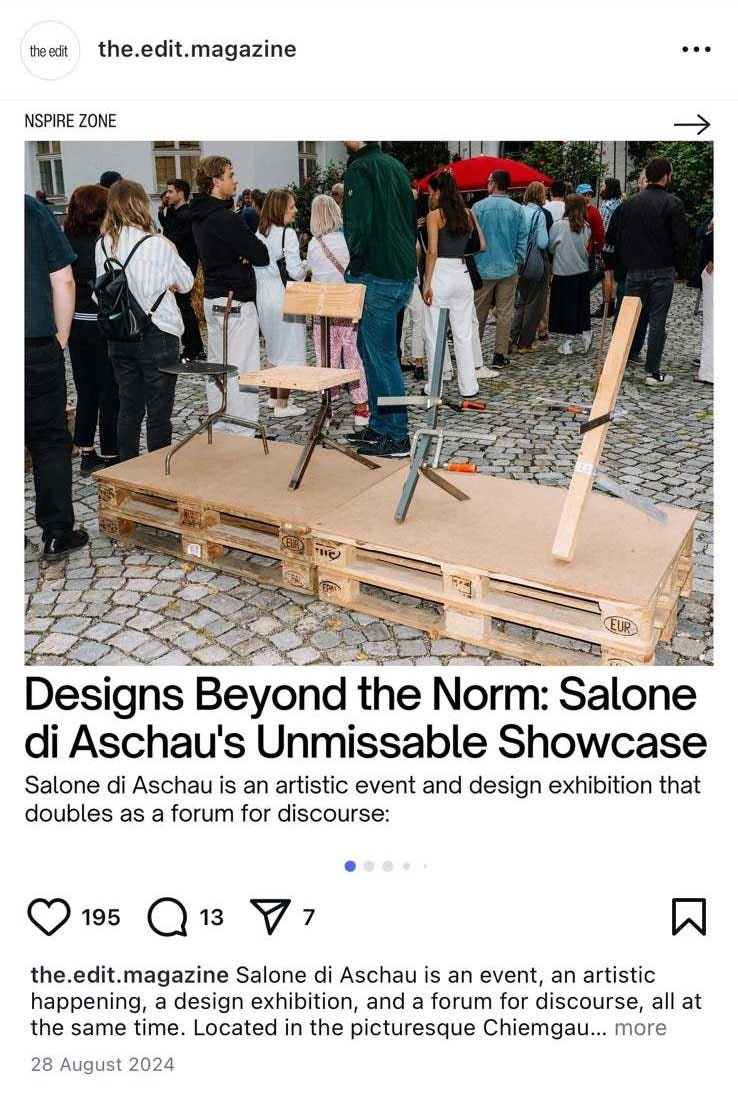

This account, named nspirezone, was also dealing with design topics, also calling themselves a magazine, also using clickbait-y headlines, also using a sans-serif font, also doing studio visits (without actually visiting people), also using one-word subtitles in their videos with yellow fill and black outlines. The signs were there, and they were obvious. They had even posted about Salone di Aschau, an event we were involved in, but which they clearly hadn’t attended.

Since the account had a bit of an amateurish feel to it, I hoped people would be able to tell the difference between us and them. Still, some of our friends and business partners liked and commented on their posts. But since the person was “just” copying how I structured certain formats, I tried to stay calm.

Furthermore, I wasn’t really sure what I could even do about it. Yes, our brand is a registered trademark in Germany and the European Union—but how could I take legal action against someone running an anonymous Instagram account, without any clear location or identity? Hiring an attorney to pursue what seemed like a vague case didn’t seem promising. And besides, we didn’t have the money for that. Founding the thing Magazine and trying to make a living from it is already expensive enough.

So, I decided to block the channel to protect my inner peace.

This copycat crossed a line

Almost exactly one year later, I was at the gym. I was just casually checking my phone between sets, when I received a message from a friend and a longtime supporter of our work. He had sent me an Instagram post: “Are they copying you?” I immediately had a feeling who he was talking about, even though I couldn’t see the post myself, as it came from a blocked account. My first inner reaction was: Yes, they are. But you know what? I don’t care. They do it badly, and I don’t want to waste my energy on this.

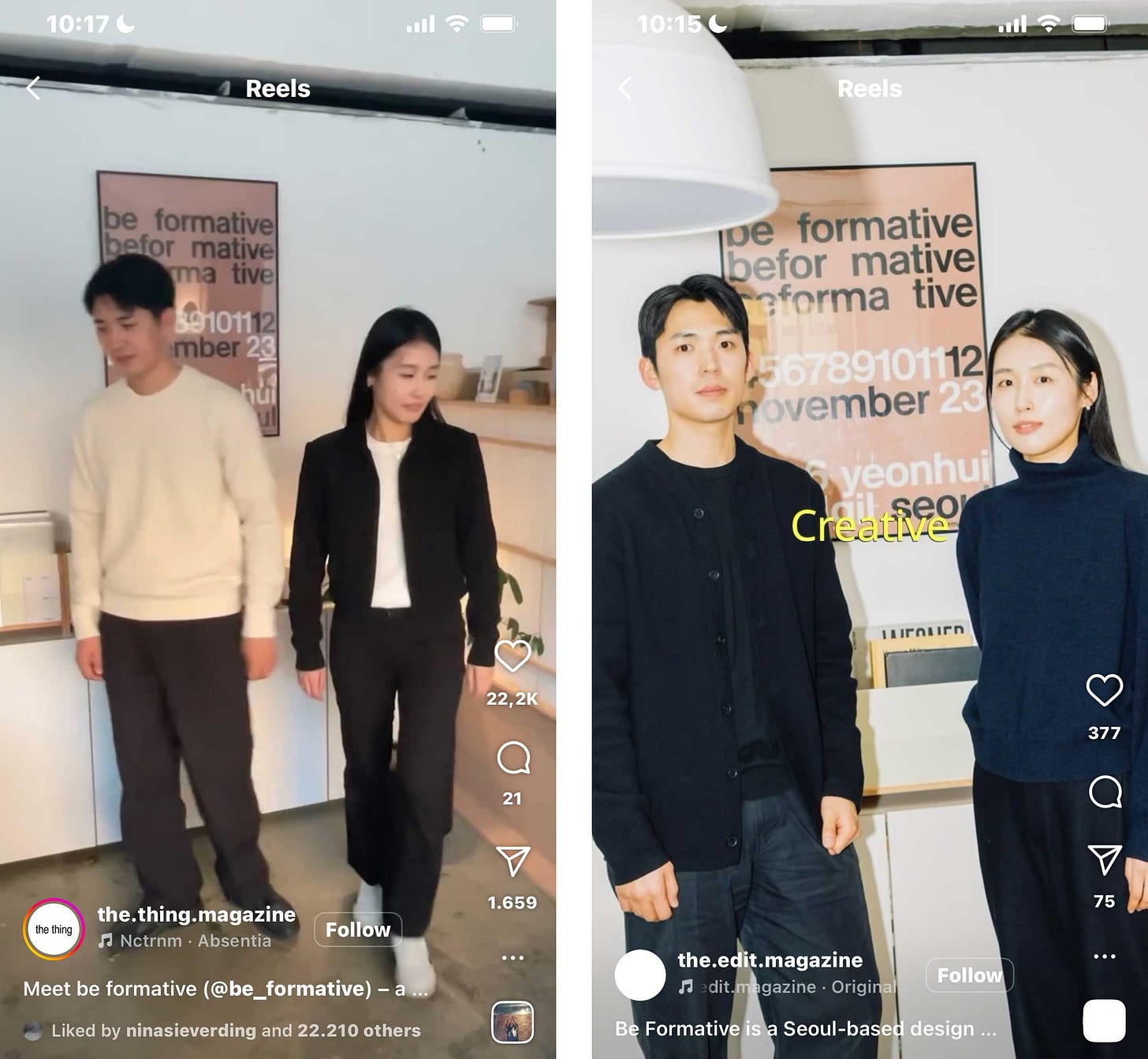

But then he sent me a screenshot of the post. In the quiet calm that followed us blocking them, the account had slowly transformed into a near-exact copy of ours. Yes, the typographic details still felt a bit amateurish, but the overall appearance had become strikingly similar. The cherry on top? A post announcing the “redesign” with a new logo and renaming of their magazine to the.edit.magazine.

I get that digital formats are notoriously difficult to protect from a copyright perspective. But a brand is more than just a layout, a topic or a way to cut videos. It’s the sum of all visual and conceptual elements: tone, rhythm, perspective. And I felt that this person was blatantly trying to be us.

I’m a big true crime fan. There’s a familiar pattern among habitual fraudsters: Once they’ve gotten away with it a few times, they start to believe in their own success. There’s always a moment—one final, greedy step—where they could have chosen to stop and continue unnoticed, but instead, they overreach. To me, I think that was what happened here. This person had gotten away with copying us just a little—and probably would have kept going indefinitely, had they not taken that one extra step of renaming them, using a similar font, logo and … name.

For me, that was the tipping point. I just couldn’t ignore this anymore. This wasn’t flattery. This wasn’t “the sincerest form of imitation.” This was theft—of time, energy, ideas, and identity.

What are the options?

It took my loyal intern exactly one minute—and a quick talk with a chatbot—to figure out who the person behind the account was. This person had been documenting every step of their so-called “success story” on LinkedIn, using their real name and profile picture. When I finally saw who it was, I felt oddly relieved. It wasn’t someone from my creative circle or my design or publishing ecosystem. It was a man based in Egypt.

But his location also meant that our legal options were much more limited. Yes, our brand is a protected trademark in the EU. But enforcing those rights internationally would mean a long, exhausting, and expensive legal process with an uncertain outcome. And no—I’m not naive enough to expect Meta to stand up for my rights or act on this in any meaningful way.

I started thinking in a different direction: What is it that we do best? Digital storytelling. If legal tools weren’t a strong option, maybe changing what people like to call “the narrative” could be. So I created an info post about the incident, using our reach to call out the one thing holding his fragile setup together: his fake image of integrity.

Do we have to protect him?

Part of this post was to call him out—his channel, but also him as a person. The internet can be a place of anonymity. However, that only applies if one chooses it. Our copycat chose to be present as a person—not on Instagram or directly linked to his channel, but on LinkedIn. There, he posted about his great “successes” and marketing talents.

Still, we chose not to show his face or publish his full name. Why? Because as people who follow a certain moral code, we don’t see him as a person as the only problematic part of this equation. And yet, because he acts publicly and seems to operate with a different moral compass than we do, we felt it necessary—up to a certain point—to hold him personally accountable.

Furthermore, this was the only way we could pressure him at all. Like I said before, we don’t have the money nor the capacity to defend us legally. Attacking his integrity and him as a person, seemed to us like the only way we could protect what we created.

Was this the right thing to do?

As soon as we had published the post and the first reactions started coming in, I knew we had made the right decision. Not only did we receive a wave of support and solidarity from our followers–many people told us they had been completely misled. They had genuinely thought the copycat account was affiliated with us, or even that it was us.

One Instagram user even shared that they had a prior exchange with the copycat. Apparently, the account started out by reposting other people’s content without asking for permission.

For us, the post also marked a kind of legal and public clarification: we made it clear that we were here first, that our ideas are being copied, and that we will defend ourselves if we’re pushed to do so.

I’m not someone who enjoys conflict. (I’m quite a people pleaser if you can believe it.) I actually hate that someone’s behavior forced me to become a person I don’t particularly like being. Maybe that’s just the world we live in. Reach (and converting reach into money) is obviously a big part of this story. That’s also what makes me a little sad. Because the thing Magazine has always been something I genuinely enjoy doing for its cultural and social value. I love visiting creatives in their studios. I love analyzing trends and trying to understand what they’re really about. I love connecting the dots between design, art, and political forces.

That’s also what I told myself when the copycat started doing what they were doing: They can’t take away the real-life experiences I’ve had. And they can’t take away my expertise as someone who’s worked in design and creativity for a long time. But does that mean I shouldn’t defend what I’ve created?

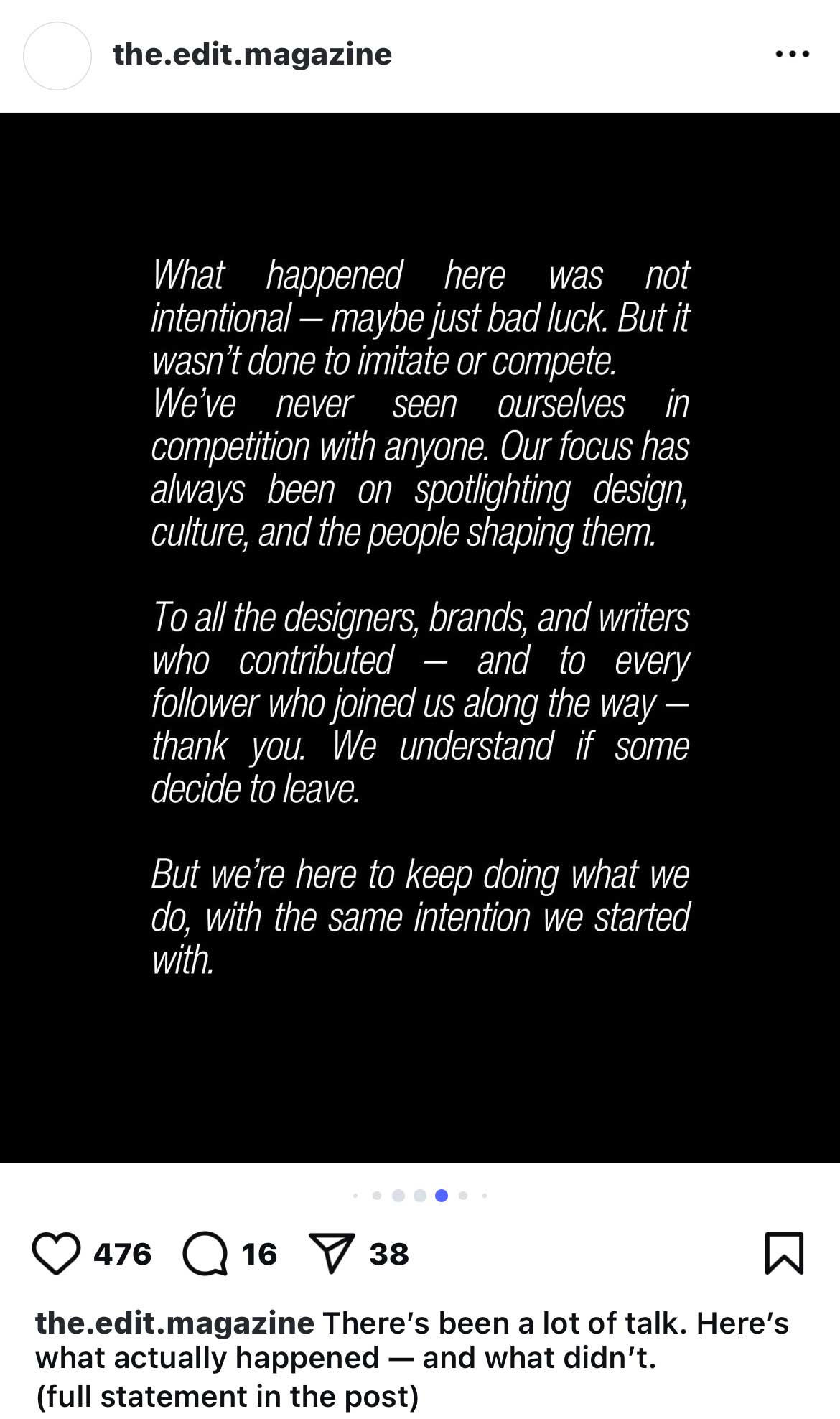

Another moment that confirmed we were right to speak out was the response the copycat posted after we went public: imho possibly the worst nonpology ever. They claimed any similarities were purely coincidental and even tried to use the fact that we blocked them as “proof” of their innocence. Honestly—no further comment needed.

Moving On

the thing Magazine was a surprising success, but it didn’t come out of nowhere. I put a lot of time and passion into it. Ideally, it benefits not just us, but also the creatives we feature and the wider community by helping to move the conversation around design forward. Of course, the bigger issue also lies in the toxic structures of platforms and how they enable this kind of behavior. But still, if the copycat hadn’t gone so far as to copy our name and logo, I probably would have let it go. In the end, this is also about individual decisions. We all have choices, some better, some more privileged than others, but copying someone else’s entire creative identity is rarely the beginning of a sustainable career—at least that’s what I think.

xoxo,

Anton

(co-founder of the real thing)

wow what a great read. And extremely frustrating. This happened to me ages ago, and I sent a simple cease and desist letter over instagram and it worked (typically people don't want to find out how serious you are).

But... our entire calendar concept was copied by a big publication after we had multiple meetings with their founder to work together. The emails stopped and suddenly.. they launched a design calendar. I think you can guess who. It was sad and demoralizing, especially since I can see that they are one of the top viewers on our instagram page (I can show you how to check "stalkers" who don't follow you on instagram...). However, it also showed me that we are good enough to copy. It's frustrating nonetheless. Thank you for sharing!